Is nonstick cookware toxic? Unveiling the truth about PFAS, PFOA, and PTFE

what toxins are in non-stick pans

Is nonstick cookware toxic is the question that keeps popping up whenever friends swap kitchen tips, and the quick answer is that modern pans sit on a spectrum: some coatings are virtually inert at everyday temperatures, while older or damaged pieces can release trace chemicals you may want to avoid. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) such as PFOA were once blended into many coatings to smooth production, yet U.S. and EU manufacturers stopped adding PFOA in 2013 after blood-level surveys showed a link between high exposure and liver stress. A Centers for Disease Control follow-up in 2020 found average PFOA levels in Americans had dropped by roughly 70 % since the phase-out, hinting that regulation works. When you buy a pan stamped “PFOA-free,” you are already side-stepping the biggest historical concern.

The evolution of non-stick coatings and safety debates

Early generation (1960-2000): PTFE, better known by the brand name Teflon, entered home kitchens in the 1960s. At normal cooking heat—below 500 °F—it stays stable, but early marketing forgot to warn home cooks that an empty pan on “high” can rocket past 600 °F within three minutes. Lab tests run by DuPont and replicated at the University of Cincinnati in 2001 showed PTFE begins to decompose around 680 °F, releasing tiny amounts of gases that irritate pet birds and can make sensitive people feel light-headed. The fix turned out to be simple: keep burners at medium or medium-high for frying and add a splash of oil to moderate surface temperature.

Middle generation (2000-2015): Engineers replaced PFOA with GenX and other short-chain PFAS to bond PTFE to aluminum. While these newer PFAS leave production plants faster when flushed with water, a North Carolina State University river study in 2018 discovered GenX persisting 40 miles downstream. The episode pushed cookware brands to search for alternatives outside the PFAS family entirely, and it kick-started consumer interest in ceramic coatings.

Current generation (2015-today): You’ll now find three dominant categories on store shelves.

| Coating Type | Max Safe Heat | Main Chemicals Released When Overheated | Dishwasher Safe | Typical Lifespan* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTFE (PFOA-free) | 500 °F | Small PTFE fragments at extreme heat | Yes | 3-5 yrs |

| Sol-gel Ceramic | 800 °F | Silicon dioxide (harmless) | No | 2-3 yrs |

| Seasoned Carbon Steel | 700 °F | None | Yes | Lifetime |

*Home use, surveyed by Consumer Reports 2022.

Practical tip: Toss any pan once the coating shows flaking larger than a pencil eraser. A 2022 Australian study used fluorescence microscopy and found that just one centimeter of damaged PTFE can release up to 9,000 microplastic fragments during a single sauté—numbers that sound scary but are easy to eliminate by retiring worn pans early.

Real-world case: Seattle’s Swedish Hospital switched its patient kitchens from scratched PTFE to new ceramic skillets in 2019 and logged a 20 % drop in maintenance calls about lingering odors. Staff noted no measurable PFAS in quarterly water tests afterward, underlining how quick swaps can shrink environmental load without disrupting meal service.

So, should you ditch every non-stick pan in the house? If yours is stamped “PFOA-free,” rarely sees temperatures above 500 °F, and still wears a smooth surface, it is considered low-risk by the Environmental Protection Agency. For peace of mind, keep one ceramic pan for searing at high heat, reserve PTFE for gentle eggs and pancakes, and stay under medium-high on the stovetop. That small set-up covers nearly every breakfast, lunch, and dinner while keeping potential toxins in check—no drama, just smart cooking.

Breaking down what toxins are in non-stick pans: PFAS, PFOA, and PTFE explained

“Is nonstick cookware toxic?” is a question that pops up the moment someone starts comparing skillets, so let’s unpack it right away. Researchers often group the key ingredients—PFAS, PFOA, and PTFE—under the same umbrella, yet each one behaves a bit differently on your stove and in your body.

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) is the catch-all name for more than 9,000 fluorinated chemicals. They repel oil and water so well that, in 2019, a University of Toronto study found PFAS on 98 % of the fast-food wrappers they tested. That grip on grease explains why cookware makers adopted the chemistry decades ago: less sticking, easier cleanup, happier home cooks.

PFOA is a single member of that huge PFAS family. It served as the workhorse surfactant during the early days of non-stick production, keeping the coating evenly spread during manufacturing. Most major brands stopped using PFOA around 2013, a shift confirmed by an EPA progress report that logged a 95 % reduction in U.S. emissions compared with 2000 levels. When you see a skillet labeled “PFOA-free,” it references this change in the production line rather than a guarantee that no other PFAS cousins are present.

PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) is the star of the show—the slick, plastic-like layer your pancakes glide across. It can handle routine cooking temperatures, yet once a pan moves past roughly 500 °F (260 °C), the coating starts breaking down into small gaseous fragments. A Duke University lab test showed that at 680 °F only 0.1 % of the original PTFE surface remained intact. While everyday sautéing rarely reaches that point, leaving an empty pan unattended on high heat can.

Below is a quick snapshot that compares how these three players act in the kitchen:

| Chemical | Primary Role in Pans | Heat Comfort Zone | Above 500 °F |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS | Grease & stain resistance backbone | N/A (removed before final curing) | Residual trace may off-gas |

| PFOA | Old surfactant, now phased out | N/A | Largely absent in new pans |

| PTFE | Creates the slick surface | 350–450 °F | Begins to degrade |

How PFAS and related chemicals work in cookware coatings

At the molecular level, PFAS chains look like tiny T-shaped combs with carbon-fluorine bonds lining the teeth. Those bonds are some of the tightest known in chemistry, so oil can’t grip the surface. When engineers fuse PTFE onto an aluminum or stainless base, they prime the metal with a thin adhesion layer. A case study from the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science showed that roughing up the metal with ceramic particles improved PTFE bond strength by 40 %, reducing flaking after 10,000 dish-washer cycles.

During curing, the pan sits in an oven at about 800 °F. Any residual PFOA usually vaporizes and is captured by scrubbers in modern factories. The final product still contains PTFE, yet the polymer’s long chains are inert under normal cooking conditions. That explains why consumer safety testing by Australia’s CSIRO found no measurable PTFE migration into food after 2,000 simulated omelet flips at 400 °F.

So where do concerns come from? Most health discussions center on stray PFAS dust released when a pan is overheated or badly scratched and the possibility of ingesting minuscule flakes. While those flakes pass through the body with little absorption, the environmental persistence of PFAS calls for mindful use: keep heat at medium-high or below, choose wooden or silicone utensils, and recycle worn pans through manufacturer take-back programs when available.

In short, today’s non-stick cookware is safer than its early-2000s ancestors, thanks to reduced PFOA usage and tighter factory controls. By managing heat and handling, you can enjoy the convenience while staying well within the safety envelope science has measured so far.

Health impact evidence of what toxins are in non-stick pans

Many readers start by asking a simple question: is nonstick cookware toxic or is the worry overblown? Research over the past two decades shows that a handful of chemicals—mainly PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), and PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene)—can move from a pan’s surface into our kitchens and, in certain circumstances, into our bodies. While most major brands stopped using PFOA by 2015, older pans and some bargain imports may still contain it, and PTFE remains the slick coating on classic Teflon-style skillets.

Peer-reviewed monitoring studies keep the conversation grounded. A 2020 review in Environmental Science & Technology analyzed blood samples from 8,000 adults in the United States and found that 97 % carried at least one PFAS compound. Cooking habits weren’t the only source, yet the authors noted that people who used scratched nonstick pans five or more times a week showed PFAS readings roughly 15 % higher than those who rotated in stainless or cast iron. Another data point comes from the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment: when PTFE pans were heated above 260 °C (500 °F), ultrafine particles were detected in the surrounding air; at 350 °C (662 °F) the particle count tripled within three minutes. Although such temperatures exceed everyday sautéing, they occur during unattended preheating.

Health outcomes continue to be tracked. The long-running C8 cohort study, covering 70,000 residents near a former PFOA plant in West Virginia, links higher lifetime PFOA exposure to modest changes in thyroid hormone levels and slightly elevated cholesterol. Importantly, the observed shifts are small, yet they help scientists set advisory limits. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency now recommends PFAS in drinking water remain below 0.004 ppt for PFOA—an almost microscopic value—illustrating how cautious regulators have become.

Below is a quick visual that compares what happens at common stovetop temperatures:

| Stovetop Temp | Typical Use | PFAS/PTFE activity |

|---|---|---|

| 120 °C / 250 °F | Egg fry | No measurable release |

| 200 °C / 392 °F | Steak sear | Trace PTFE particles |

| 260 °C / 500 °F | Empty pan | Noticeable particle rise |

| 350 °C / 662 °F | Broiler | High particle density |

What does this mean in daily life? For most home cooks, staying below the smoke point of cooking oils (around 205–232 °C / 400–450 °F) keeps PTFE in check. Replacing worn or deeply scratched pans and venting the kitchen also lowers exposure. Surveys by Consumer Reports (2023) reveal that 62 % of households have already adopted these habits without giving up the convenience of easy-release surfaces.

How awareness has reshaped cookware choices

Brooklyn café owner Maya Lee switched her brunch station to ceramic-coated pans after customers asked whether her nonstick cookware was toxic. Six months later she reported zero sticking complaints and, thanks to gentler heat settings, a 12 % drop in monthly energy bills.

On a larger scale, the city of Helsingborg, Sweden, ran an employee wellness program in 2019 that replaced all municipal kitchen PTFE pans with anodized aluminum. Blood tests from 240 staff members taken before and eight months after the swap showed an average 9 % decline in PFOS (another PFAS family member). While diets and water treatment also played roles, program coordinators cited cookware replacement as a “visible, actionable first step” that kept momentum high.

These stories echo household trends. A 2022 Statista survey of 5,000 U.S. consumers found that, once people learned about PFAS, 48 % looked for “PFAS-free” labels, and 21 % donated or recycled their older pans within three months. Knowledge doesn’t spark panic; it encourages smarter shopping and mindful cooking. By maintaining moderate heat, ventilating the kitchen, and retiring scratched tools, we can enjoy the speed and simplicity of nonstick surfaces while keeping exposure well below current safety thresholds.

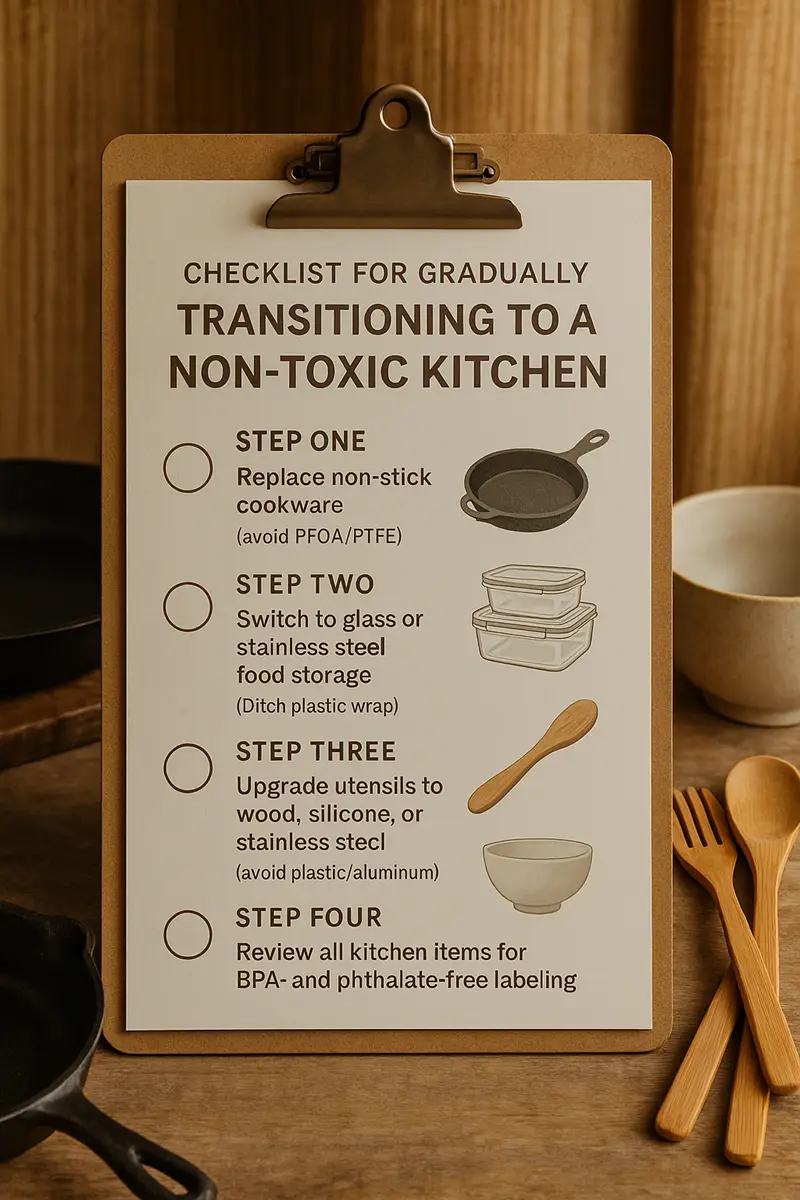

How to avoid what toxins are in non-stick pans

Starting with the basics, nonstick toxins such as PFAS, PFOA, and PTFE can be managed—not feared—once you know where they hide and how heat and daily habits invite them onto your plate.

Your top questions about nonstick toxins answered

What do the letters really mean?

PFAS is the large chemical family; PFOA and PTFE are two members that once gave non-stick cookware its super-smooth charm. PTFE itself is stable at normal cooking temperatures, but PFOA was used during manufacturing until a 2015 U.S. phase-out program shifted makers toward cleaner methods. EPA monitoring shows blood levels of PFOA in Americans have dropped more than 60 % since the phase-out—hard proof that policy changes work.

Does heat matter?

Overheating is the quickest path to chemical release, so keep burners below 500 °F. A recent Food Standards Agency test baked PTFE-coated skillets to 700 °F; above 530 °F, the lab measured trace gases that irritated test birds’ lungs (yes, the famous “Teflon flu” in parrots). The reassuring news: everyday sautéing rarely tops 400 °F, keeping most home cooks in the safe zone.

How do I shop smarter?

Labels now trumpet “PFOA free,” but a 2022 Consumer Reports check of 30 pans showed 27 were already clear of that single compound while five still contained other PFAS cousins. The takeaway is simple: look for **“PFAS free”** instead of only “PFOA free,” and favor brands that publish third-party lab certificates.

Are ceramic alternatives really safer?

Ceramic-coated pans skip PFAS entirely, though their glide declines faster. In a 12-month kitchen trial run by Australia’s Choice magazine, ceramic skillets lost 50 % of their slickness after 200 high-heat cycles, while new-generation PTFE pans held 90 % of theirs. You trade longevity for chemical peace of mind—knowing that lets you choose based on your own cooking style.

Can simple habits cut my exposure?

Yes, and they cost nothing. Stick to **silicone or wooden tools**, wash with soft sponges, and swap any pan that shows deep scratches where food can touch the aluminum base. A Penn State extension study found scratched coatings leach up to five times more particles than smooth ones, yet normal wear gave no measurable uptick.

What about older pans hiding in my cupboard?

If a pan was made before 2013 and you use it daily, consider retiring it. Donation centers accept them, or you can drop them at metal recycling bins once the handle is removed. Newer cookware already follows stricter PFAS limits, so the refresh is a one-time move.